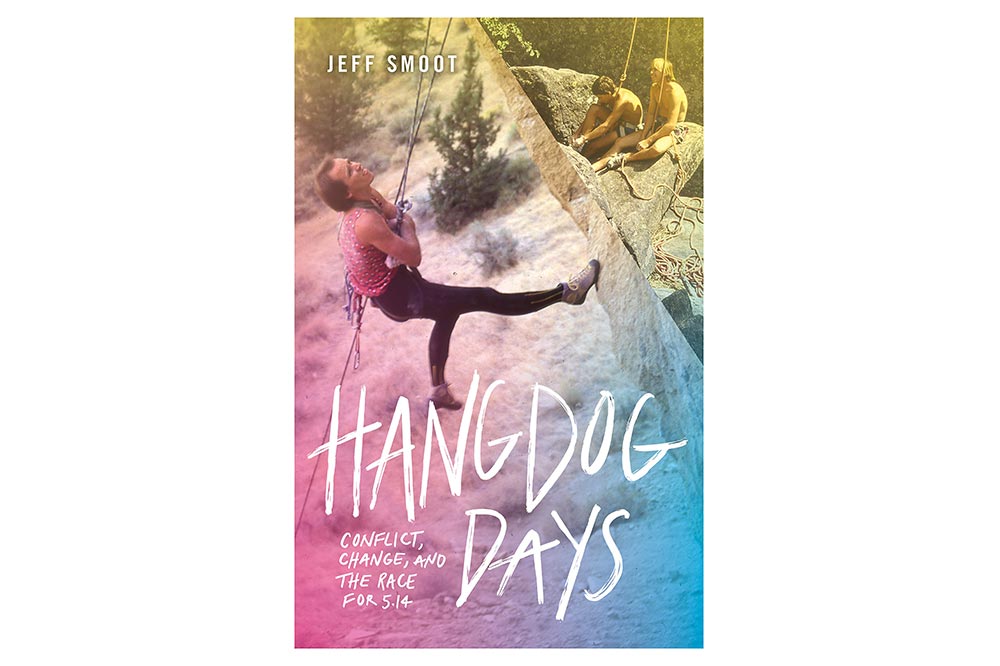

Hangdog Days: Conflict, Change, and the Race for 5.14

Jeff Smoot

Mountaineers Press, Spring, 2019

Reviewed by David Smart

Mountaineers Press, Spring, 2019

Reviewed by David Smart

When I began climbing in the late 70s, the Gunks and the limestone cliffs of Ontario sported many more fixed pitons than they do now, not many bolts because there wasn’t really a way to make them very solid anyway, and 5.11 was really hard. In fact, my teenage friends and I used to discuss whether we would ever even be able to climb a 5.11. Of course you never really knew unless you climbed such a route in Yosemite, Boulder, or the Gunks. Everywhere else was “local climbing.” Yosemite, with its flawless, easily protectable rock, set the tone for what comprised proper style in climbing: ground-up, on sight, placing only clean protection. Or mainly clean protection. Unless you were on a big wall, where anything went. It worked great in Yosemite, but on limestone there were compromises.

Like most young climbers, I got to Yosemite as soon as I could. In ’78 and ’79, I unwittingly saw the last years of its great age of world ethics domination. At 19, I had dropped out of suburban life and followed the money west to Calgary, where I worked for the autumn and winter and headed to Joshua Tree National Monument in the early spring to climb. By 1982, in Joshua Tree, change was in the air, even as John Bachar, John Yablonsky and friends drifted free-solo up their favourite 5.12s ad infinitum. Between them, on the harder climbs, younger climbers who had come from “local climbing” to drink from the well of the California rock mystique were getting on harder and harder routes. Often working them first, as had the locals, but getting visibly better as the weeks went by.

Notable among the Americans were a group of Oregonians, including Alan Watts, Alan Lester and Bill Ramsay. Another team often seen trying the hardest routes, and, after much effort, climbing them, was from Wyoming. Todd Skinner was a strong climber who was never seen on anything but the hardest routes. He was on the short side, had thin blonde hair, a great smile and got along with everyone, even the inevitable climbing curmudgeons. His climbing partner was a tall Wyoming friend named Paul Piana. I could not have known it, but these two groups of climbers, with increasing help from others, in the face of a lot of vocal, authoritative, published and spoken opposition and vandalism, and sometimes, in spite of themselves, transformed North American climbing in the 80s.

Like every movement, great or otherwise, they needed their own way of distributing their Pravda. They found it in the energetic, prolific and up-to-date output of the author of Hangdog Days, Washington climber Jeff Smoot.

In Hangdog Days, Smoot tells the story of how he fell in with Skinner, and to a lesser degree, the Smith Rocks Crew from Oregon, and cheered them on as they introduced hangdogging (resting on the rope to figure out moves) before a first ascent and pre-placing protection or cleaning routes on rappel as legitimate techniques.

Smoot discusses Skinner’s personality, drive and magnetic attraction as he emerges as the lightning rod and leader for changing climbing. He also discusses his time editing the new magazine, George Bracksieck’s Rock and Ice, which championed what would later become known as sport-climbing, while the older American mag Climbing, at first opposed it.

Skinner’s transformation from a regular denizen of the rock-climbing scene to an impresario of a new ambitious style of climbing and presenting climbing (with his cowboy hat and toy six-shooter belt) is reported on in detail. I personally found it a little camp that Skinner, who I met before his cowboy persona, would sign posters, “Hey pilgrim, keep climbing…” Smoot, once the Boswell of Skinner, admits now that there were doubts about whether he and Piana free climbed every move of the Salathe wall, as they claimed. Smoot’s journey from Skinner’s acolyte-once-removed (the function of acolyte par excellence having been filled by Piana) to a realistic assessment of his hero is sensitively written. The wistful paragraphs where he allows that the desire for a secure adult life eventually undercut the anarchistic pleasures of rock climbing are some of the leanest and best I have read on the subject.

And yet, even after marriage, home and career, Smoot is drawn to revisit some of the people and places of his climbing journey, not out of nostalgia, so much as of a desire to understand himself. The resulting descriptions range from semi-comic insight into Piana’s present-day occupation as a truck driver in Gillette, Wyoming, (“I spent all my money climbing,” he says), and, tragically, Todd Skinner’s death.

Although the book is a veritable who’s-who of climbing in the eighties, with snapshots of John Bachar, Jerry Moffat, Lynn Hill, Pete Croft, Scott Franklin and dozens of others, I was also struck by how the great change in climbing in the 80s created local climbing heroes who would once only have been considered cranks wasting their time outside of Boulder, Yosemite and the Gunks. Chris Oates and Judy Barnes in Ontario, Porter Jarrard in the Red River Gorge, others in Rumney, New River Gorge, Wild Iris, American Forks Canyon and a hundred climbing areas, built modern climbing with the tools and ideas of Watts and Skinner, and the people came.

Books about Himalayan climbing epics continue to dominate the imaginations and rosters of publishers and book festivals, regardless of the similarity of the accounts and how little these climbs did for anyone but the climbers. Yet, as a direct result of the people and climbing Smoot describes, we have sport climbing, gyms, comps, bouldering as we know it, and so many other things that were once unthinkable and that now form the bedrock of all serious climbing efforts. As such, I highly recommend this sensitive and fascinating account to anyone interested in how we got here.

Like most young climbers, I got to Yosemite as soon as I could. In ’78 and ’79, I unwittingly saw the last years of its great age of world ethics domination. At 19, I had dropped out of suburban life and followed the money west to Calgary, where I worked for the autumn and winter and headed to Joshua Tree National Monument in the early spring to climb. By 1982, in Joshua Tree, change was in the air, even as John Bachar, John Yablonsky and friends drifted free-solo up their favourite 5.12s ad infinitum. Between them, on the harder climbs, younger climbers who had come from “local climbing” to drink from the well of the California rock mystique were getting on harder and harder routes. Often working them first, as had the locals, but getting visibly better as the weeks went by.

Notable among the Americans were a group of Oregonians, including Alan Watts, Alan Lester and Bill Ramsay. Another team often seen trying the hardest routes, and, after much effort, climbing them, was from Wyoming. Todd Skinner was a strong climber who was never seen on anything but the hardest routes. He was on the short side, had thin blonde hair, a great smile and got along with everyone, even the inevitable climbing curmudgeons. His climbing partner was a tall Wyoming friend named Paul Piana. I could not have known it, but these two groups of climbers, with increasing help from others, in the face of a lot of vocal, authoritative, published and spoken opposition and vandalism, and sometimes, in spite of themselves, transformed North American climbing in the 80s.

Like every movement, great or otherwise, they needed their own way of distributing their Pravda. They found it in the energetic, prolific and up-to-date output of the author of Hangdog Days, Washington climber Jeff Smoot.

In Hangdog Days, Smoot tells the story of how he fell in with Skinner, and to a lesser degree, the Smith Rocks Crew from Oregon, and cheered them on as they introduced hangdogging (resting on the rope to figure out moves) before a first ascent and pre-placing protection or cleaning routes on rappel as legitimate techniques.

Smoot discusses Skinner’s personality, drive and magnetic attraction as he emerges as the lightning rod and leader for changing climbing. He also discusses his time editing the new magazine, George Bracksieck’s Rock and Ice, which championed what would later become known as sport-climbing, while the older American mag Climbing, at first opposed it.

Skinner’s transformation from a regular denizen of the rock-climbing scene to an impresario of a new ambitious style of climbing and presenting climbing (with his cowboy hat and toy six-shooter belt) is reported on in detail. I personally found it a little camp that Skinner, who I met before his cowboy persona, would sign posters, “Hey pilgrim, keep climbing…” Smoot, once the Boswell of Skinner, admits now that there were doubts about whether he and Piana free climbed every move of the Salathe wall, as they claimed. Smoot’s journey from Skinner’s acolyte-once-removed (the function of acolyte par excellence having been filled by Piana) to a realistic assessment of his hero is sensitively written. The wistful paragraphs where he allows that the desire for a secure adult life eventually undercut the anarchistic pleasures of rock climbing are some of the leanest and best I have read on the subject.

And yet, even after marriage, home and career, Smoot is drawn to revisit some of the people and places of his climbing journey, not out of nostalgia, so much as of a desire to understand himself. The resulting descriptions range from semi-comic insight into Piana’s present-day occupation as a truck driver in Gillette, Wyoming, (“I spent all my money climbing,” he says), and, tragically, Todd Skinner’s death.

Although the book is a veritable who’s-who of climbing in the eighties, with snapshots of John Bachar, Jerry Moffat, Lynn Hill, Pete Croft, Scott Franklin and dozens of others, I was also struck by how the great change in climbing in the 80s created local climbing heroes who would once only have been considered cranks wasting their time outside of Boulder, Yosemite and the Gunks. Chris Oates and Judy Barnes in Ontario, Porter Jarrard in the Red River Gorge, others in Rumney, New River Gorge, Wild Iris, American Forks Canyon and a hundred climbing areas, built modern climbing with the tools and ideas of Watts and Skinner, and the people came.

Books about Himalayan climbing epics continue to dominate the imaginations and rosters of publishers and book festivals, regardless of the similarity of the accounts and how little these climbs did for anyone but the climbers. Yet, as a direct result of the people and climbing Smoot describes, we have sport climbing, gyms, comps, bouldering as we know it, and so many other things that were once unthinkable and that now form the bedrock of all serious climbing efforts. As such, I highly recommend this sensitive and fascinating account to anyone interested in how we got here.

Join the discussion of this and other climbing related stories at https://ontarioclimbing.com/forum/